Plains Culture in the Bison Era

The Region

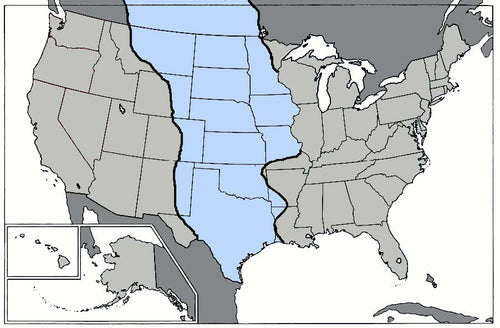

Spanish explorers called it mar de hierba, sea of grass. The French called it prairie, meaning

“large meadow.” When Indians occupied the Great Plains of North America before the advent

of white settlers, the grasslands covered more land than any other type of herbage, whether

forest or desert. The Plains are great indeed, a high plateau extending for 1,125,000 square

miles including three provinces of Canada and about one-third of the United States covering

parts of 10 states: Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Nebraska, Kansas, Colorado,

Oklahoma, Texas and New Mexico.

(Wikipedia)

Diversity

When we think of Native Americans living on the Plains in the 18th and 19th centuries, the Sioux, Cheyenne, Blackfeet and Comanche typically come to mind. But over 30 different tribes lived there and spoke languages derived from different indigenous language families. In terms of religious beliefs, customs and way of life, “They were as varied culturally as the European immigrants who settled the North American continent, “according to the National Park Service. Most tribal members were nomads who followed and hunted the bison. Others were semi-sedentary farmers who hunted bison too.

Housing

Nomadic Indians like the Sioux and Blackfeet lived in tipis (usually spelled teepees), conical

tents formed by long, crisscrossed wooden poles covered with buffalo hide and built by

women. The tipi, easily put up and broken down with portable parts, was ideal for nomadic

life.

The agrarian Indians, like the Wichita and Caddo of the Southern Plains, lived in permanent,

beehive-shaped houses thatched with grass. They were sometimes 50 feet tall and could hold

two or more families.

A young Oglala girl sitting in front of a tipi, with a puppy beside her, 1861

(Photo by John C. H. Grabill, Wikipedia)

The Wichita and other agrarian tribes lived in beehive shaped houses thatched with grass and

surrounded by fields of maize other crops.

(Lithograph of Wichita village, probably in Oklahoma, between 1850-1875, Smithsonian Institution)

FAMILY LIFE: ‘Not to Have but to Be’

Tribal family life was characterized by paring existence down to its simplest terms. This nonmaterialistic

philosophy was succinctly expressed by Charles Alexander Eastman (“Ohiyesa”),

an Eastern Dakota physician and author. “’Not to have but to be’ was his [the Indian’s] national

motto,” he said.

While specific religious beliefs varied among the tribes, they shared in common the idea of a

spiritual connectedness that wove all of life together, the religion called animism. Theirs was a

cooperative community characterized by mutual respect and strictly prescribed roles of men

and women. Marriages were often arranged, and the groom’s side was expected to provide a

dowry to compensate for the loss of the woman’s labor. Some tribes, like the Lakota and

Navajo, allowed polygamous marriages. Children were cherished and treated with kindness;

discipline was exercised through praise and reward rather than physical punishment. From infancy, they were taught to refrain from showing emotion as a sign of strength. Elders were

highly esteemed and held important roles, with the women helping with chores and childcare

and the men esteemed as teachers, wise mentors and spiritual counselors.

Survival depended on the tribal members’ ability to obtain food, and this required efficiency,

skill, strength and focus. Thus, duties were defined by gender. The men were the hunters and

protectors. Their sons trained to hunt from an early age, learning to use bows and arrows

sized to fit. They learned the arts of defense and methods of war. When they reached puberty,

it was time for a rite of passage. This was the vision quest, a spiritual journey from boyhood to

manhood. In some tribes, young women also engaged in the quest. While details varied

among clans, the initiate would go into solitude, pray and fast, and hope for a spirit guide to

appear in a dream and help direct his destiny. To further commemorate his step into adulthood,

the teenage boy got to go on his first hunt with the men. “The Indian boy,” wrote Eastman

in Indian Child Life, “enjoyed such a life as almost all boys dream of and would choose

for themselves if they were permitted to do so.”

Girls were trained to prepare for the domestic and maternal responsibilities of adult life. They

learned chores and household skills, and like most girls everywhere, they played with dolls for

fun and to teach them childcare. The dolls given to Comanche girls were made of deerskin,

with their clothes fashioned by their little owners. Girls used child-size tools and were taught

to sew, cook and butcher and prepare game.

Dolls and cradleboards. Miniature cradleboard is probably Chippewa or Ojibwa. The

tribal nations in the Minnesota region used floral designs in the beadwork. Neutral-colored

deerskin dolls are Plains Indians.

(Ancient Ozarks Natural History Museum)

Miniature cradleboard

(Ancient Ozarks Natural History Museum)

Child’s toy tipi - Sioux

(Ancient Ozarks Natural History Museum)

Indian clothing was simple, practical and made from the hides of animals they hunted, like

deer and bison. Men wore long shirts, breechcloths, long leggings, a belt and moccasins, and

in the winter, bison robes. Women wore long dresses, short leggings and moccasins. Clothes

were made generally by the women who first tanned the hides, then cut and stitched them

into the desired garment. Feathers, quills and other natural materials added decorative beauty

to their clothing, and later, glass and seed beads acquired from trading with Europeans.

For recreation, Plains Indians played a variety of sports and games. Some, like dice, were used

for gambling. After a hard day of labor, women were the ones who most often played games

of chance and sometimes stayed at it all night long. The dice were made from different materials,

like bison rib bones or the pits (stones) of plums. Other games, like archery, stick ball,

and hoop and pole were for strength and dexterity. Both women and children used a stick

ball to play a game called Shinny, now known as Lacrosse.

Osage Bowl & Dice Game

(Brooklyn Museum)

The duties of food gathering were divided, with the men primarily hunting bison and other

game and the women performing domestic chores. In semi-agrarian tribes, women tended to

crops – most typically the Three Sisters, maize, squash and beans.

Before Native Americans hunted on horseback, they tracked the bison on foot and used two

primary group hunting methods: the “buffalo” jump and the “buffalo” impound. In the first,

the men would draw a herd to a cliff and using a decoy, cause the animals to tumble to their

death below. The hunters would choose a young man known to be a fast runner, who would

disguise himself with bison hides and imitate the distress cries of a bison calf. As the bison

moved toward the edge, other runners disguised as wolves came up behind the herd, and

the frightened beasts would fall one on top of the other. The impound strategy involved luring

the animals into a wooden enclosure and killing them with bows and arrows.

Once they acquired horses, first from the Spanish in the late 1600s and then as horses became

widespread among the tribes, the Plains Indians hunted by horseback for greater advantage

and far less danger than methods on foot. They chased the herds on galloping, well-trained

horses and shot lances or salvos of arrows into the animals’ sides. Emil Her Many

Horses, a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian, notes, “When

horses were introduced, the modes of hunting changed. A favorite hunting horse could be

trained to ride right into the stampeding buffalo herd.”

Buffalo Hunt: A Numerous Group

(Hand-colored lithograph by George Catlin, 1844, Wikimedia Commons)

The contributions to culture and everyday life made by women were incalculable. As noted

on Indians.org, “They were more than just mothers of the tribes’ children. They were builders,

warriors, farmers, and craftswomen. Their strength was essential to the survival of the tribes.”

From being responsible for gathering materials to create their family’s dwellings to joining

their men in the bison hunt, they demonstrated strength and resourceful leadership. After the

hunt, they skinned, butchered and cooked the animal. Other tasks were collecting firewood,

cooking, sewing and repairing clothing and shoes.

“The wife did not take the name of her husband nor enter his clan, and the children belonged

to the clan of the mother. All of the family property was held by her, descent was

traced in the maternal line, and the honor of the house was in her hands. Modesty was her

chief adornment; hence the younger women were usually silent and retiring: but a woman

who had attained to ripeness of years and wisdom, or who had displayed notable courage in

some emergency, was sometimes invited to a seat in the council.”

Hattie Tom, Apache, 1899

(Wikimedia Commons)

We are happy for you to use the content on our historical pages if you will reference the source, www.BenjaminLeeBison.com and send an email to explain your intended use to Jessi at [email protected]

Sources

John L. Dietz and Elwyn B. Robinson, "Great Plains." Encyclopedia Britannica, November 17, 2020.

https://www.britannica.com/place/Great-Plains

“The Plains Indians,” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/arKcles/000/the-plainsindians.

htm#:~:text=There%20were%20more%20than%2030,region%20in%20pursuit%20of%22bison

Brett and Kate McKay, “Lessons from the Sioux in How to Turn a Boy into a Man,” June 19, 2020, Art of

Manliness.com. https://www.artofmanliness.com/articles/lessons-from-the-sioux-in-how-to-turn-a-boyinto-

a-man/

Sally Painter, “Family Life in the Culture of the Plains Indians,” Love to Know. https://family.lovetoknow.-

com/cultural-heritage-symbols/family-life-culture-plains-indians

“Native American Women,” Indians.org. http://indians.org/articles/native-american-women.html

“Bison Bellows: Indigenous Hunting Practices,” National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/articles/bison-

bellows-3-31-16.htm

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Indian Child Life by Charles A. Eastman. https://www.gutenberg.org/

files/25907/25907-h/25907-h.htm

Want to learn more about the history of bison in North America?

Join our newsletter for articles, facts and news on the American bison